I was 25 when I first arrived in Japan after an epic land journey. That’s an age by which manhood should, in theory, be fully attained and embraced, and indeed the journey had included romantic encounters and adventures that seemed to fit the narrative of my now being an adult, properly grown up. But looking back at it now, even including the last few decades, the entire structure of my so-called adult life has been built on somewhat shaky psychological foundations.

I referred to it in a previous post, how I’ve sometimes had a sense of being a boy at the adult’s table, and from that perspective I could easily look at the 22 years I lived in Japan as a series of missed or wasted opportunities, times when I lacked the emotional maturity, security and confidence to take full advantage of a variety of things that life brought my way, whether that was in the form of friendships, relationships or job and business opportunities. Fortunately (or unfortunately) I had just enough intelligence, charm and energy to get by alright, helped in no small part by being a tall, white male who picked up the local language quite quickly, in a country where those qualities alone were enough to make you a superstar if that was your dream and you had the balls to chase it. It wasn’t and I didn’t.

I arrived in Tokyo just when the boom in learning English was being properly commoditised for the first time, in the form of big chain schools. I spent a decade and a bit teaching English, first at one of those chain schools and later at a private junior & senior high school. I was good at it and it paid quite well but my heart was never fully in it, it wasn’t really fulfilling. Along the way, I had also got my first Apple computer and has started doing digital illustration work for a foreign startup that made English language-learning software. That job was one of those opportunities that, had I been more mature, I could have made much more out of. What happened instead was that I combined it with the teaching gig and, as a result of burning the candle at both ends, I ended up burning out completely and had to step away from it for a while. But at that point I had picked up some experience in all things digital, based on which I started my own website, Japan Zone, in 1999.

By this time I’d been in Japan almost a decade. I’d had plenty of romantic encounters but, apart from an Australian woman I lived with for a year, they were mostly fleeting. I was definitely overcompensating for my late start. Just a month after I created the Japan Zone website, I met C. Our relationship, which would go on to become an 18-year marriage with three children, was in part built on the fact that we came from similarly dysfunctional families and we saw in each other the possibility to make sure “the buck stops here.” We understood each other and promised that we would not let what had happened to our parents happen to us.

What we failed to recognise was the fact that two people whose lives are built on shaky foundations can only support each other for so long. We tried marriage counselling, both in Japan and later in Ireland, but any progress we made would eventually be eroded by old patterns of behaviour. It is only since we split up a couple of years ago that we fully realised that the vital step that we had failed to address was to resolve our own issues as individuals and that, without doing so, we were doomed to repeat the patterns we had learned from our parents. Fortunately, once the trauma of the split had eased, we were both able and ready to finally start doing that work. In my case, one result of that process was the creation of the Father Lessons project.

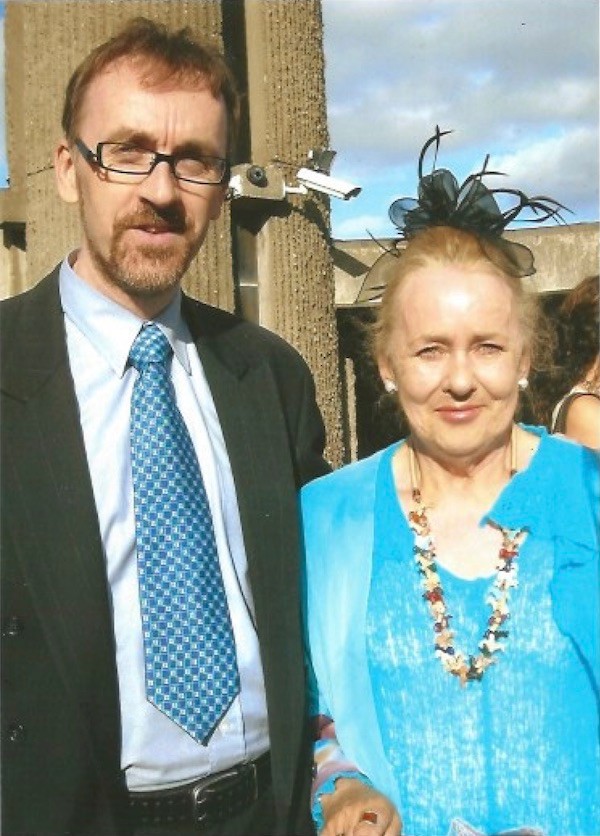

I need to jump out of the timeline and go back a few years to mention one episode along the way that had a huge impact on me. I was back in Ireland in 2009 for my brother’s wedding, just me without the family. I guess weddings and funerals tend to put people in a generally heightened emotional state, which is what I assume was the trigger for what was to happen on this trip.

Backtracking even further, going back decades, I had always carried a degree of resentment toward my mother about incidents in the dim and distant past, in particular the circumstances of my birth, the breakdown of my parents’ marriage, and her demonisation of my father. I had wanted to address all of this, express my feelings about it all, but on every trip home over the years I never seemed to find a way in to that conversation.

And so I found myself at home in Malahide with my mother after the wedding. I don’t remember the details of the conversation that led up to it, but at one point my mother made a remark about how she felt C hadn’t been very welcoming to her when she came to visit us in Japan when our youngest was born. For some reason this fairly innocuous remark flipped a switch in my head and I flew into a rage. Again, I don’t remember the details of what we said. All I do remember was that I was totally consumed by decades of resentment and anger. I would have left the house there and then, but it was very late at night so I stormed upstairs and packed my bag. I called my father and was in tears as I explained what had happened. I swore I would never speak to her or set foot in that house again. Early the next morning, I left and went to my younger bother’s flat. At some point over the next day or two, he persuaded me to talk with my distraught mother on the phone. Tearful and apologetic, she begged me to come out to Malahide for a talk, saying she wanted to tell me things she’d never been able to before.

The next day, my mother, the elder of my brothers and I found ourselves sitting around the kitchen table. I wish I had a recording of that conversation, just to be able to properly remember it in all its detail. But essentially she told us her life story, about how she and my father had met, how she had got pregnant, how they decided to go to London to have the baby and put it up for adoption with a Canadian agency, and how she had been told by her parents that she wouldn’t be welcome back with a baby. And then how, once I had been born, they were unable to go through with their plan and decided to take me home and face the music. So much of this was completely new information to me that I just sat and listened in a state of shock. But as she spoke, I had a physical sensation that felt as if a huge weight had been literally lifted from my shoulders. Afterwards, for the first time in years, I was able to say with sincerity to my mother that I loved her. It was a transformative experience, for me and for our relationship. Without it, I doubt I ever would have been comfortable moving back to Malahide as we did a few years later.

It would be dishonest to claim that our relationship was fully restored. I still had so much work to do on myself (as I still do) that completely opening up remained difficult. But our relationship was vastly improved. As I said, it made moving from Japan to Malahide in 2012 a natural and happy transition (for me, if not everyone else in the family). I could spend more time with her and, in spite of her poor health, she had a chance to develop something of a relationship with her grandchildren. Sadly, we were on the move again to London just two years later, but at least I was close enough to make it home regularly, especially in March 2018 when her rapidly deteriorating health meant she couldn’t hold out any longer. She remained on a ventilator until I could arrive on the last flight from London and passed away peacefully a few hours later.

My mother was a beautiful, immensely kind and thoughtful person, whose passion for life and colour was only partially diminished by years of poorly understood mental health issues and chronic illness. If I hadn’t spent almost my entire adult life running away, I might have been able to help reduce her hardship. But as I mentioned above, we did at least manage to salvage something in her last few years and I know that gave her some peace of mind. Writing, rewriting and finally delivering her eulogy to extended family and friends in St. Sylvester’s church, trying to find words that would do justice to a hard life well lived, was one of the hardest things, and one of the most important things I’ve ever had to do. I’m not sure how I managed not to choke (until the very end) – I suppose my decades of practice shutting down my emotions finally came in handy!

The couple of years since then, in a sense fuelled by my mother’s death and my divorce, have at least led me to finally take action and start doing “the work” of self development. Being in a regular men’s group and having all the different forms of support that it brings has been a huge help. I’ve experienced new forms of self discovery and healing. And this new journey, or new chapter in the overarching journey that is a life, has no destination or goal as such. There’ll be no point at which I’ll be “fixed” or “cured”. Hopefully I’ll just be happier, more joyful, more present, more alive.

I realise that I’ve just skimmed over an almost 30-year period of my life in a few short paragraphs. But that’s not an attempt to avoid anything. This was never meant to be a memoir, just an overview to give some context as to why and how I came to a point where I felt compelled to create this project. I could edit and rewrite it multiple times, as I did with my mother’s eulogy…no, I think I’ll just leave it there.